- Good Ones

- Posts

- The "Shit Happens" Cinematic Universe

The "Shit Happens" Cinematic Universe

Breaking down the difference between "premise" and "narrative" in Civil War and more

If these ideas are intriguing to you, maybe you wish to subscribe to my newsletter.

Other writing:

How much should you spend on a kitchen knife? at Bon Appétit

The joy of a fancy dinner at Tone Madison

Sometimes, there’s a witch

Alex Garland’s Civil War is a cipher. Not in the “secret code that uses an algorithm to unlock its message” sort of way. The film, rather, is a cipher in the old sense: a nonentity. It operates as a trick mirror designed to reflect back your priors, fulfilling meaning only in what you, as the viewer, decide is at stake. It was designed that way on purpose, by the way. As stated in an interview with the Financial Times:

To avoid perpetuating such divisions, Garland removed certain elements from his movie: political triggers that might stop viewers from watching with an open mind. Similarly, throughout our meeting, he words his answers very carefully so as not to appear partisan or polemical. “If it was just another piece of inflammatory bullshit, then that really would be a failure,” he says. “Because, however it looks, the film is actually trying to find a non-polarised point of agreement. Its whole intention is to be able to have a conversation.”

If that sounds a bit like mealy-mouthed both-sidesism, it’s because it is. Garland strives to be an iconoclast who defies categorization, even if it means his political movie is devoid of any politics. He goes on in the same interview to denounce extremism while touting journalism as a way for a population to fight back against an authoritarian leader. That almost feels like he’s taken a strong position, if not for the fact that his film clearly hates journalists. Civil War hates journalists so much that I watched multiple journalists come away from that movie second-guessing their entire life’s output.

It’s an easy message to take away. As the story follows four journalists on their way to interview the sitting president before separatists take Washington, D.C., the audience gets to watch how dead inside each of the main characters is. They hem and haw about how to get the ultimate scoop, they second-guess their motives, they bicker and complain, and when Sammy, the elder statesman (played by Stephen McKinley Henderson), dies, they struggle with what the point of it all was. Then, of course, they carry on with their plan to rush the White House, embedded with the Western Forces (a separatist nation comprised of California and Texas).

The scoop trumps all, Garland’s movie says, boldly and loudly. And what’s the actual scoop they get? An authoritarian third-term President pleading “don’t let them kill me” right before he’s executed. A movie that treasured journalism might have generated better insight for the final interview with a deposed despot. Not to mention that Kirsten Dunst’s Lee dies protecting the aspiring photojournalist Jessie (Cailee Spaeny) on their way to get said scoop. All glory to the scoop, no matter how hollow it may be, no matter how many lives it claims. Lee’s sacrifice, as well, is shot and framed as if it’s the only good thing she’s ever done in her career.

If Garland is so sure that journalism is the answer to fight extremism, then why does it feel like his movie absolutely hates journalists?

The answer, of course, is that Civil War, as a movie, doesn’t really have anything to say. It’s vaguely anti-war, showing how nasty it can be, but it also acknowledges that the only way to oust a dictator is by force. It pillories journalists as selfish and boorish, but the director claims journalism as the tool of the people. It wants us to fear extremism, but it won’t name what extremism is or dig into the policy of its third-term president. In the same interview, Garland states that Civil War is “about populism, and populism is a substantial step towards extremism.” Except we never see either side of the war actually pandering to the populace. What’s populism without a populace? What’s a movie without a perspective?

In the grander scheme of things, Civil War belongs to the “Shit Happens” Cinematic Universe. On paper, there’s a premise—what if a civil war broke out?—and on screen, the filmmaker rarely gets past the premise into an actual narrative. Things happen on screen, we’re not really sure why, we don’t know what it’s supposed to mean, and the filmmaker doens’t seem to really understand either. The movies are shot beautifully, capture images and scenes that play for big emotions, but ultimately don’t have a perspective that leaves you leaving the theater having felt anything true. These are the “pure vibes” movies that beg audiences to ascribe meaning to the images they saw on screen.

These movies, in the “Shit Happens” Cinematic Universe, often end at the moment that should be their beginning. The most interesting idea in Civil War isn’t “How do you get to a President before he’s executed,” it’s “Well, the president’s dead. Now what.” The movie spends nearly two hours establishing its premise, but it never fully develops a narrative. Getting to the White House is the premise; figuring out what wartime journalists do after the execution is the narrative. By cutting off the movie right as it opens up, Garland is telling the audience, “Well, you figure it out.” Without an actual narrative to connect with, though, most of the figuring out is entirely invented for each viewer.

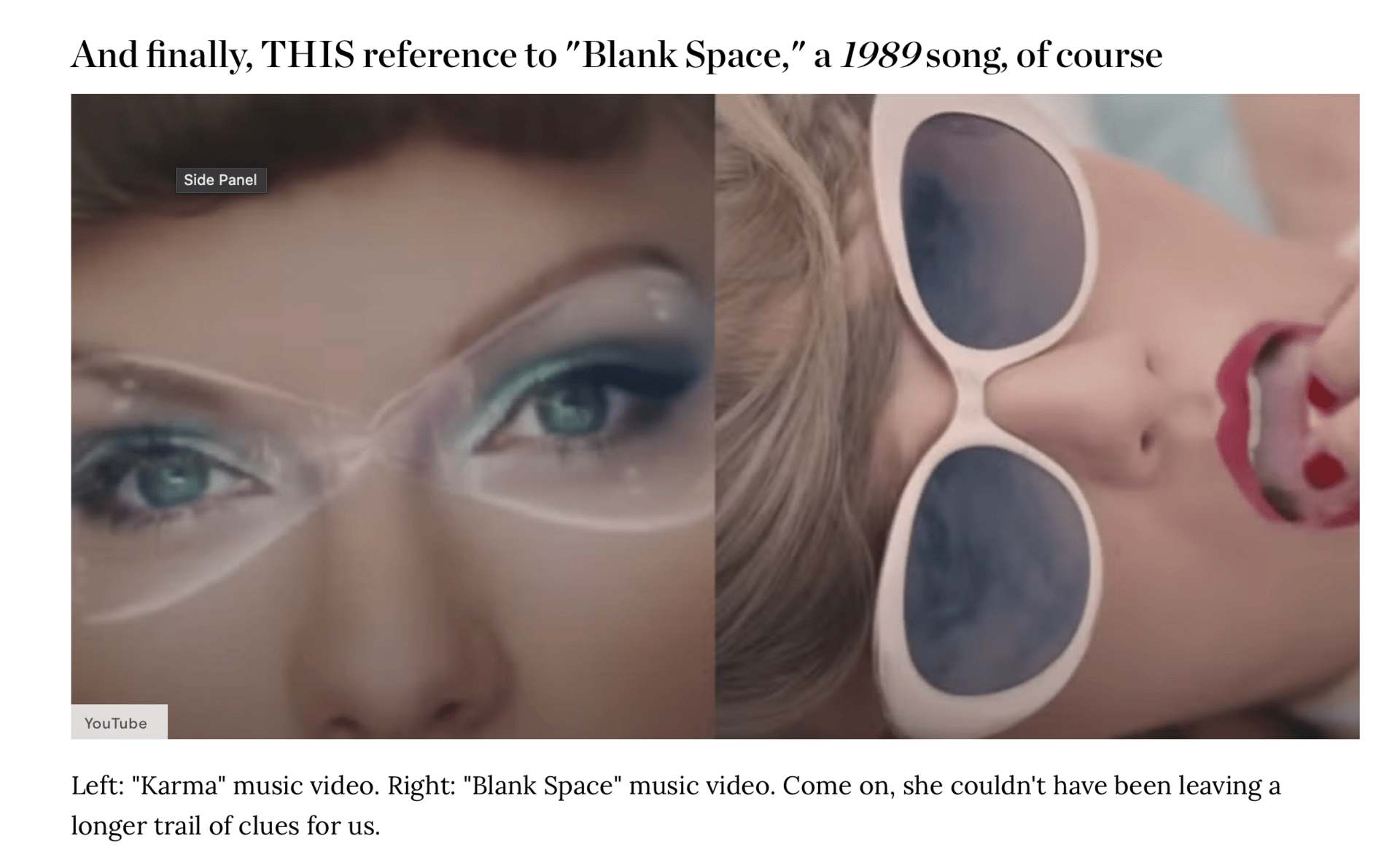

The closest equivalent I know of is when an online fandom views a pop star doing something banal and declares it to be some version of higher communication. This happens frequently with Taylor Swift fans, who often comb through her works looking for unique patterns that reveal a direct missive to only a core group of superfans, as revealed in this Cosmopolitan article. Sure, Swift leaves intentional hints for her fans from time to time, but then there’s also this:

The “Shit Happens” Cinematic Universe, because of the work left for the viewer to complete, tends to resonate with people in strange ways. But while modern audiences might leave a movie like Decision to Leave pondering what it means because the director wanted to provoke thought and feeling, the “Shit Happens” Cinematic Universe leaves viewers wondering what it meant because the director didn’t guide them to anything. We’re left, then, with artifacts that are more movie-shaped without actually being a coherent, start-to-finish movie.

Civil War isn’t the only offender. Garland’s other directorial efforts are also stuck in vibes mode, where the questions “What if robots were smart?” or “What if men were bad?” are asked at the climax instead of answered. Directors like Ari Aster, Robert Eggers, and Emerald Fennell also make movies that get swept up into the “Shit Happens” Cinematic Universe, where a series of events plays out until the movie just stops. Dozens of millennials left Saltburn wondering what all of its provocative scenes were for, when the answer is, plainly, to show provocative scenes to an audience without much else there.

If you include Zach Cregger in the mix, you can start to unravel the “Sometimes, there’s a witch” subgenre, where a movie plays out multiple terrible events until it’s revealed that, actually, there was a witch the whole time. The VVitch is a classic example, but Hereditary, Weapons, and others fall flatly into this grouping. Scene by scene, these movies have good acting, beautiful sets, intriguing dialogue, well-framed shots, and then, well, I guess there was a witch this whole time, and that about wraps it up. Shit happens. The witch isn’t always a witch; it can also be a monster. That gives you Barbarian and Saltburn wrapped up tidily.

“Sometimes, there’s a witch” is a premise. It’s not a narrative. The narrative is what happens after you find out there’s a witch, and the characters have to contend with this new turn of events. Reflecting back to Decision to Leave as a foil, the premise of the movie is “What if a detective falls for a manipulative suspect?” It takes half the runtime to establish, but then the true narrative of the movie begins: the characters grow, change, and develop as they contend with the events unfolding. The questions audiences are left with aren’t “What does this movie say?” but rather “What does this movie say about desire? What does this movie say about survival?” The perspective of Park Chan-wook is apparent, even if you’re left pondering how the movie resonates with you.

The “Shit Happens” Cinematic Universe revels in big gestures, shocking violence, and scene-specific tension to grab viewers’ attention. But when the credits roll, it’s hard to imagine what the director wanted the audience to experience other than Goldmember’s resounding chorus: “Isn’t that weird?” All of these new movies are big and empty, indebted to German Expressionism without understanding how to manipulate exaggerated visuals and performances into anything but shock and awe. Say what you will about conservative, reactionary, pro-military propaganda; at least it’s an ethos.

It’s impossible to break down these arguments without dredging up the dreaded beast of “media literacy.” When used as a cudgel by film bros to bully detractors into liking their favorite movie, the phrase is weaponized to justify the lack of content on the screen. But media literacy, at its core, is not whether or not you “get” a movie; media literacy is a set of tools used to analyze the content of what is in front of you. Mainly: if it’s not on the screen, it’s not part of the movie. If it is on the screen, it begs to be analyzed. If a charater says one thing but the movie shows something else, both parts have to be considered in the film’s analysis. The contradictions in Civil War cancel out the movie’s meaning. Self-selecting dialogue in support of journalism to make a point—”We do this so other people can make their inferences”—ignores all the ways the camera treats the journalists as scum in the movie.

It’s an issue that Robert Eggers’ Nosferatu also struggles with. The pinnacle of the movie is Lily-Rose Depp’s Ellen choosing to sacrifice herself to save her husband and the rest of the city. In that moment, it’s presented as Ellen exercising her own agency as she’s torn between the whims of modern society and the thrall of the vampire who claims her soul. Except, well, she doesn’t really have agency in that moment. The vampire has brought plague and pestilence to her town because he wants to possess her. He wants to possess her because she called out, at a young age, for “a guardian angel, a spirit of comfort... anything,” and Count Orlok (Bill Skarsgård) was the one who answered. With that scene in consideration, it’s Ellen’s own fault that the vampire is tied to her psychically. That makes her decision later less about her seizing her own power and more about her needing to accept punishment for her childhood whims. In short, Ellen wanted premarital sex and now must die for it. In other words, shit happens.

I think it’s clear, at this point, that I don’t like these types of films. They leave me hollow. But lots of people watch different types of movies for all different types of reasons. Horror movies get away with their emptiness because for many people, the titillation is the point. On the latest The Flop House episode, Stuart Wellington recommends Weapons by saying, “This is a horror movie that, in some ways, to me, like Barbarian, isn’t really about anything, but is a wild, exciting, horror movie ride.” It’s tricky when the sheen of a prestige drama clouds the intent of a supernatural slasher movie, but maybe it’s okay if the point of Hereditary is just to decapitate a child. It’s a harder pill to swallow when these big, empty movies are supposed to be saying something provocative, which is why Civil War crumbles under scrutiny.

Still, Civil War captures action and excitement in individual scenes that are evocative. Everyone remembers the weight of Jesse Plemmons’ “What kind of American are you?” scene. The Santaland sniper scene also captures the frantic energy of facing an unknown, omniscient enemy. Garland’s chase cam footage through the West Wing is exciting and kinetic. There’s value in finding entertainment in things that are entertaining. Inventing a narrative for a film that lacks one, however, is an entirely different beast.

If someone hands you a blank page and you fill it with letters, that’s your story. Not theirs. I don’t find it productive to fill in a movie’s story for myself—that’s what I have writing for. I’d rather figure out how to tell my own stories. At least in my stories, I know they’ll have a perspective. It’ll just be on me to make sure that the reader sees it, too.

Read

Simplicity by Mattie Lubchansky

Sloppy by Rax King

I went on a major book haul at the excellent bookstore across the street from my house, snagging new releases I’ve been meaning to snag for a bit. I tore through the new graphic novel Simplicity by Mattie Lubchansky in about a day, and can’t stop thinking about how powerful it was. I’m a sucker for alternative future speculative fiction, where the reader has to contend with how the world turned out the way it did, and I wasn’t quite ready for how Mattie was going to pivot that angle of the story. I don’t want to say much else, because even an attempt at a summary might ruin the magic of letting the story unfold as you go, but Simplicity is about love, lust, power, responsibility, struggle, and solution. Go buy it and read it.

I also started reading Rax King’s second essay collection, Sloppy. When I first read Tacky, I lost my shit. I don’t think there’s a modern writer out there more confident in their voice on the page while maintaining an extremely technical grasp on essay structure. Rax is truly a savant: her writing gives you exactly the information you need at the exact moment you need it for each piece, and her voice carries you through tales of addiction, grief, joy, and everything else under the sun. If you’ve ever wanted to write, you should read Sloppy.

Watch

Twisted Metal, Season 2 on Peacock

I’m a big fan of loud, sloppy TV that’s engaging, silly, thoughtful, and violent. I also love that you get to just sorta turn off your brain for most of it. Twisted Metal is a great little TV series that feels like TV, but since it’s on a streamer, it gets to push boundaries of violence, gore, and action. Season 2 ups the action while sacrificing some of Season 1’s excellent storytelling through world-building, but it’s worth it for some of the most energetic driving you’ll see on camera this year.

Listen

Canyon Lady by Joe Henderson

Joe Henderson is a great tenor sax improviser, but he also straddled the line of the late 60s into the early 70s when players started transitioning into composers. Canyon Lady was recorded around the same time as The Elements, his ambitious answer to A Love Supreme, featuring John’s widow Alice Coltrane on harp, though it was released two years later. While The Elements showcased how daring Henderson was in his compositions, Canyon Lady leans heavily into big brass sections and Latin rhythms, with only one Henderson original taking up space on its runtime. It’s a fascinating album, but also an incredible mood setter for when you’re feeling those pink sky evenings.

Consume

Sparkling Water

I just refilled my refillable 5LB CO2 tank for $20, and now I’ve got another full year of carbonating my water and chugging it nonstop. I love it. It’s low waste, adds flair to your afternoon workday hydration, and lets you lean into something fun in the evening if you’re avoiding drinking. If you’ve got a soda machine but don’t want to support a horrendous company, look up refillable options and attachments. It’s way cheaper, and you can support your local CO2 and dry ice company.

Artwork by Ashley Elander Strandquist. You can view her illustration work here and check out her printing business here.